Kevin Ruck has sent the foundation his father Ronald’s hand-written notes of his service with the 75th Anti Tank Regiment of the Royal Artillery from September 1942 to January 1946. Born on 19 November 1923, Ronald, who joined after a year’s exemption because he was working for a building firm repairing bomb damaged houses, died in 2009.

This is his story -

Before reporting to Canterbury Barracks, I had a medical and was medically fit to do my duty for King and country. One of my friends reported on the same day but he went to the new barracks on Littlebourne Road and eventually ended up in the Glider Borne Troops.

My barrack room was on Military Road about 200 yards from where I lived. There were about 30 men in our group, and we learned to drill, march, fire a rifle and throw grenades. This lasted for six weeks; the last week we had tests to see how we performed.

I was then sent to an anti-tank training school at Catterick Camp in Yorkshire. The new anti-tank gun was the six-pounder, and we did training on this firing live ammunition at targets on the moors. This training ended at Christmas, 1942, so I came home for ten days leave.

I went back to Catterick after Christmas and then to holding camps in different areas, eventually ending up at Mildenhall, Norfolk, the area of the 75th Anti Tank Regiment which I was about to join.

The Regiment was away on a scheme (war games) for two weeks. On their return I was sent to 117 Battery which was in wooden huts in a rural area. The regiment moved to a few different areas and while at Withernsea we got the new 17-pounder anti-tank gun and an American armoured vehicle called the M10 Tank Destroyer. In appearance it looked like a tank.

The M10 Tank Destroyer weighed about 20 tons and had a 75mm gun in a movable turret. There were 60 solid shot shells strapped on the sides and six high explosive shells strapped on the turret. There was a machine gun fixed to the top of the turret as protection against aircraft, 12 hand grenades in a box and one flare gun.

There were now two regiments with the M10 and one with a towed 17 pounder. We arrived at Aldershot in spring 1944, spent a lot of time making the M10 waterproof to allow the M10 to go under its own power through several feet of water, with everyone guessing where this was going to be.

Before D-Day, as it’s now called, we moved into sealed areas which had high wire fences around, supposedly to keep it secret from the rest of the south east. D-Day happened while we were in camp. Then we moved and headed for Tilbury and the tank landing ships.

While in Tilbury we stopped for a while. We had been issued with French francs for use after landing. I put one of these in an envelope and got a sheet of writing paper. On it I wrote “Mum and Dad - Guess where?”

Several women were handing out cups of tea and I asked one of them to post it but if she thought it was wrong and that I should tear it up. There were posters all about keeping secrets. My mum and dad told me later that they got it OK. They did not receive any letters from me for about three weeks after we landed in Normandy.

So, onto the landing ships tanks or LST we got. We formed a convoy in the channel, weather lovely so we decided, the other members of my troop and I, to sleep on the top deck.

Sailing the channel at night it then started to rain. Gales were making the sea very rough and I was very seasick. After about two days of gales the weather b became clear and out at sea battleships etc were firing at the French coast.

Our LST backed on to the beach and dropped its doors and we landed, not having to travel through the sea. We landed just north of a village called Beny-sur-Mer.

While in England I was in B Troop 117 Battery and we lived in huts or empty houses, so we made friends, not always in the same troop. After landing it was months before we met up again. The M10 had a crew of five, but these were not always your friends but like a family.

We were supplied with paraffin-fired cookers and all food came in cardboard packs and all tinned. I was made cook so did all meals.

The first action or battle against the Germans started on 25 June, code name Epsom. It started at 730am, hundreds of guns firing into the enemy areas and while waiting to start you think this will be a walkover, but it was not. We moved about six miles that day.

While moving forward with the infantry there was a lot of shell fire coming at us. A hill no.112 was a next objective as the top of this hill gave a view of all the surrounding countryside. Our troop was sent to back up the infantry in case of tank attacks by Germans. There was lots of shelling and mortar fire, and we were bombed once by an American fighter bomber.

My job was to put out a large fluorescent strip to notify our aircraft that we were friendly vehicles. On our first day on the hill a jeep from HQ was to visit us but never did and later it was found that they had taken the wrong track and run into the German area. Two officers were killed, along with a sergeant and bombardier.

The next big attack was code named Jupiter. To do this the River Orne had to be crossed and it only had one workable bridge. The plan was for three divisions to attack; one was the 11th armoured, two was the Guards and three was the 7th Armoured Division.

After Epsom we drove out of area and any losses – infantry, tanks etc – were made up ready for Jupiter. While travelling to this area, which took most of the day, it was so dry that clouds of dust enveloped us. I sat out front of M10 as we had already bumped a Bren carrier and put my hand up to the driver if we get to hear anyone.

It was dark when we arrived in our allocated area, set up guards for the night and went to sleep. Next morning it was bright and sunny. We looked around and saw gliders everywhere and troops dug in everywhere; we were surprised we had not run over the trenches when arriving.

One said to us: “When you cross the Orne Bridge we are going home” - meaning England - they had landed by glider on D-Day.

Jupiter started with a massive bombing of the Germans; after a few minutes a fog of dust covered us. After the bombing up to 600 25-pounders started to shell other areas.

When we reached the bombing area it was difficult to travel because of craters and the German infantry were standing about shocked and covered with dust. Later they recorded that over five miles had been devastated, trees blasted, farms and buildings shattered, and cattle and horses killed. Further behind us, the other divisions, the Guards Armoured and 7th Armoured, could not get forward because the area was too small.

In the afternoon the Germans counter attacked with tanks using their 88mm anti-tank guns. After this the lorries in the area were pulled back and B troop, us, was covered in case German tanks progressed too far. But in the late evening the German Air Force attacked this area. I decided to brew up, got onto back on M10 for water when tracer bullets from aircraft started hitting lorries etc which then burst into flames.

I jumped off M10 and lay flat in the field (and then I made the tea). It was known later the 11th Armoured had lost about 115 tanks; some were recovered later. These losses occurred through the attacks by German tanks and anti-tank guns.

The next day we were put in a position to cover a crossroads; this was mostly fields and hedges. There was a possibility of another German attack. It was very quiet at first, another sunny day. Suddenly there was a massive explosion about 100 yds away. I went to have a look; the crater was much bigger than the German 75mm and 88 mm guns.

This carried on most of the day, some in front, some behind us. Sometimes we moved for it seemed as if someone could see us. The size of the crater suggested a large gun; there was sometimes a half hour before the next shell. We could see from our position the tall chimneys of the industrial area of Caen.

The Next day thunderstorms made all the area nearly impossible to move. About 30 square miles had been cleared of enemy.

On 22 July the division moved back over the Orne. Southward from Bayeaux it stretched into Bocage country, small lanes, thick hedges, if you went into a field, it had banks all around and tanks could not climb them. Some tanks later had metal girders welded on to push through banks, but in this awkward country the Germans were being pushed back in many places. We were in contact with American forces.

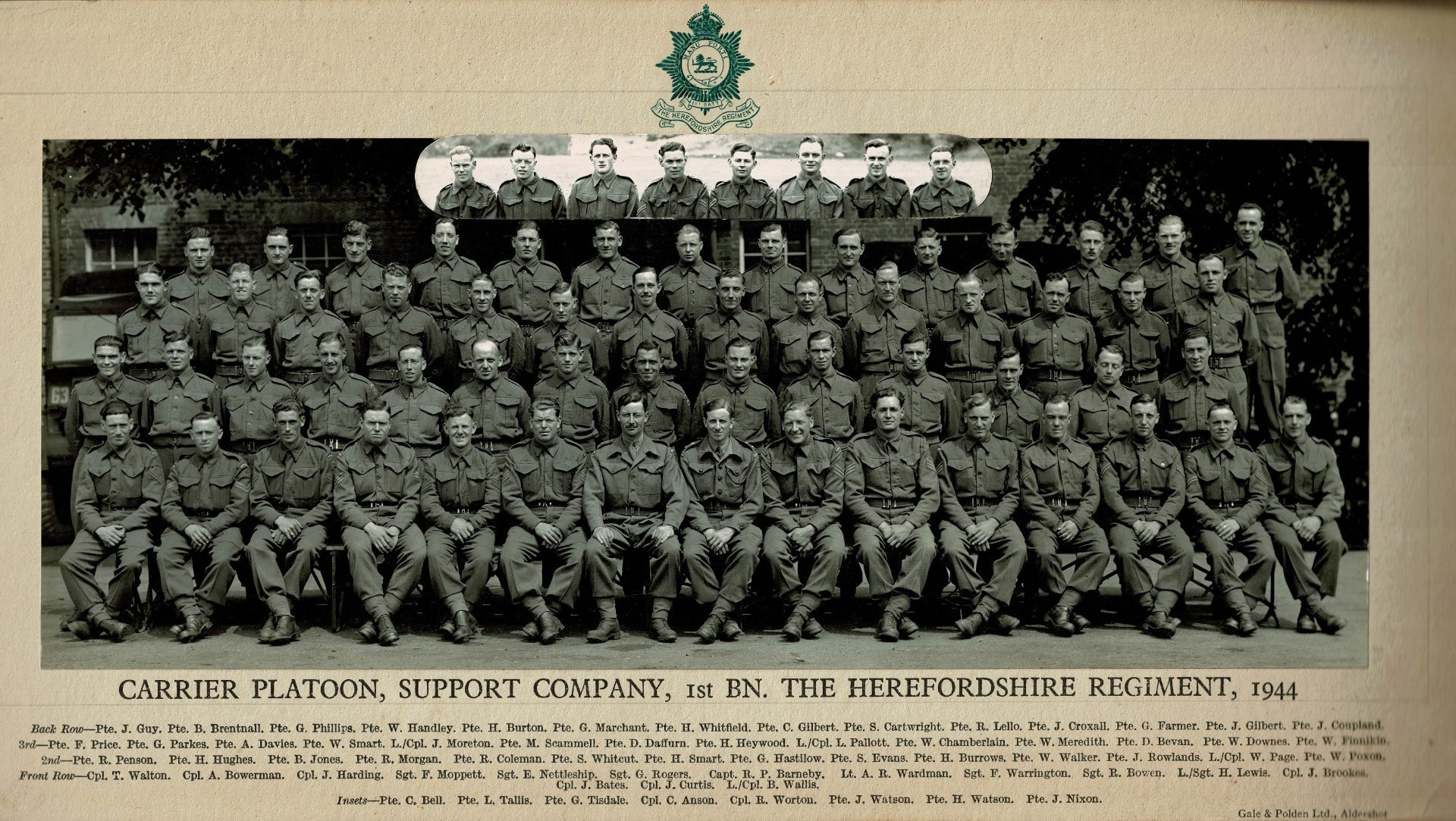

The Germans had laid many mines; these had to be cleared and slowed the progress of forward units and us. Mostly we were with the Monmouthshire Regiment and, I think, the Herefordshire Regiment. These regiments called on us if there were any threats from Germans tanks on their positions. If the Germans mounted any large attack, the rocket firing Typhon planes would attack any visible enemy tanks.

Mostly we as an anti-tank troop did not really know where we were. Our officer had the map and would position us after consulting the infantry officer regarding the best site for us. All this time I would cook meals whenever we stopped for a while or at a given position. When we first started cooking for ourselves we only had our two mess tins each, so very soon if we saw an abandoned house or farm we managed to secure pots and pans.

Going on, the Germans were now trapped in what is now called the Falaise Pocket. The allied forces had now cut off one part of the German army from the other. This was August, great weather, so the German troops tanks etc were smashed by air strikes and artillery and the lanes and roads were charred by these burning vehicles.

Just a passing fact is that we always slept outside of the M10. At first we dug a pit and then ran the M10 over it, but we then heard that German patrols at night had destroyed some tanks with a weapon called a Panzerfaust tube one metre long with a bomb at the end. When fired at close range this would destroy a tank, so we dug small trenches away from M10 and slept in these. Also, through the night we did two hours guards around M10 area.

The division kept pushing on and Amiens was approximately 30 miles in front of leading tanks and also the River Somme which the Germans would defend well to stop the division crossing.

We were refuelled late in the evening, and it was supposed to be a moonlight night but as we started to move it started to rain. We pushed on through the night and at first light saw German troop vehicles etc in the fields next to the road. They stood about totally bewildered.

Amiens was entered about 5am. A general was taken prisoner at night; apparently some German vehicles joined our columns in the dark.

The infantry who entered the town captured two bridges intact over the Somme. Over 1000 Germans were taken prisoner, including the chief of staff off the Somme Corps who were supposed to defend this area. We did not go into Amiens and after crossing the river we used a road on the outskirts of town to bypass it.

The next town which I remember was Lens. Though working with the infantry there were many villages etc that were liberated. We arrived in the outskirts of Lens late afternoon; it had rained and was now cloudy.

Later, French men came into the field in which we were positioned. They wore brown overalls and black berets and had a band on arm marked FFI which was French Forces of the Interior. One wanted my German automatic which I got from the early days of Normandy. One of our crew told him that if the Germans didn’t shoot him one of our infantry would, being dressed like he was and carrying a weapon.

After a lot of chat, he invited us to his house to celebrate the freedom of Lens from the Germans. There was a railway line about 200 or 300 yds away and he said he would meet us there about 6pm. By this time it started to rain but were met at the crossing by this Belgian man who had brought umbrellas with them. That was the biggest laugh of the evening. Three scruffy soldiers, each holding a brolly, got to his house. His wife and daughter were waiting for us and a few minutes later her fiancé arrived. The two men had got tuxedos on and the women had evening dresses and we three soldiers looked, what can I say, rough.

The house inside was grand and I thought: “This is not too bad after being under German rule for about four years,” but we had a great evening; food and champagne which they had saved to celebrate this day.

About midnight or later our host walked us back to the crossing; it had stopped raining, but it was still dark and we had had too much champagne. We would never have found it on our own.

The division was still pushing ahead but there were still quite a few small battles as the German forces were trying to hold out in villages and the roads to slow the division down. The main objects of the division were Brussels and Antwerp, the latter the most important, as all our supplies were still coming from the Normandy beach head, trucked up by convoys of lorries.

Petrol by this time was being pumped from Kent to France by pipes under the channel this being PLUTO (Pump Line Under the Ocean).

So, then it was decided that Guards Armoured would go for Brussels and 11th Armoured for Antwerp, which was further on. In the attack on Antwerp, great help came from a Belgian officer who knew the way to a bridge over the River Rupel. This was taken, so tanks and infantry entered Antwerp. They found the central park in the town heavily defended; this was overcome and in the end over 6,000 prisoners were taken and the HQ of the general of the Antwerp garrisons.

Our M10 troop entered the suburbs of the town but was not needed for any action so stayed put. A fact to be noted was that in the six days since we had crossed the Seine the division had covered 340 miles, and from Caumont some 580 miles. The Sherman tanks had done this without going on the transporter so had a good mechanical reliability, as had our M10s as they were also produced in America.

To carry on, in this dash across Belgium some German troops would stop and fight back in places such as woods, farms and rivers, so sometimes we would be way out with German forces on either side of us.

One instance was that we were in a column of infantry tanks when it was decided that our troop would protect the road from attack, so our officer positioned us accordingly. We ended up in a farm yard and were told to keep a good watch out.

About half an hour a later he called in to see us; his vehicle was a Bren carrier driver and wireless op. While talking to us, he stopped talking and was looking behind us. We turned and saw the barn door opening and out came a pole with a sack on it, followed by four German soldiers. We passed them on to a lorry taking some more prisoners to the rear.

It seemed a hectic life; we ate when we could, washed when it was possible. Our officer was very casual about how we dressed, mostly fatigues, which were baggy trousers and top and big enough to go over our battle dresses. Too hot in summer

so we wore the thinner fatigues usually. Somehow, from the start we never wore the steel helmets and nor the baggy berets.

One instance I remember well; the wireless operators were on their sets about 5.30 - 6am to receive a signal from the carrier set. All sets were tuned in to this and when OK they were locked on. Soon after this the officer appeared. I was brewing up and making tea, I had a cup with us. At this moment Jock our engineer appeared wearing a black jacket and a hat with a shiny peak, looking like a railway worker in England. The officer drank his tea, looked at Jock and said: “Sutherland, you ought to wear something British Army. If the Germans capture you, they will shoot you as a resistance fighter, especially if you are carrying your rifle.”

As the officer walked away, Jock said: “Excuse me sir it won’t be the Germans who shoot you, it will be one of your own lot.” Our officer looked at himself and said to Jock: “Yes, I see what you mean,” for he had on a German sniper’s jacket and trousers and jackboots. With these on you’d be almost impossible to see if standing in a hedge.

This was in Normandy and two of our troop were shot by snipers, a sergeant in the log and a wireless operator in the wrist. Not long after this our officer, Lieutenant Stearn, was badly injured while looking for positions for the troops to go to. It was thought that it was shell fire as we were all caught by it at this time. The officer went back to England for hospital treatment.

A complicated and dangerous process

Cathy Barker has submitted the diary of her father Kenneth (Ken) Barker, who served from 20 August 1943 to 30 October 1947 in the Royal Armoured Corps, Staffordshire Yeomanry and Royal Scots Greys.

She explains: “His mission was being involved in the complicated and dangerous process of taking fuel and ammunition to the sharp end and returning with empty jerry cans to be refilled.

“Dad emigrated to Australia in 1960 and died in Queensland in 1984. He was 20 when he voluntarily enlisted and 24 when he was demobbed. His diary account begins on D-Day and ends at Antwerp before five days rest in September. He recounts the fears and joys in the voice of a rookie 20 year old. Who can imagine their sombre wise old father at such a young and inexperienced age?

“Contrary to what he says, he hardly ever spoke of his experiences so we three daughters knew little of his service. It is a shame that by the time we knew of our father’s traumatic experiences it was too late to thank him.”

Cathy and his sisters honoured their father with a plaque on Hill 112, pictured. To honour a relative, click here.

IN A FIELD TEN DAYS AFTER D DAY

At the moment, although we still have the Nazi gang just around the corner, we are still at the same field and I haven’t very much to do which gives me time to think things over a bit. However much I try to recall in detail the events which occurred and actions I have been in since D plus ten, when we landed, I am bound to omit some of them.

Also, when I look back on some incidents, they seem less terrifying than when they happened, while others I wonder how I took so calmly.

I’m afraid I shall become a bore when at last I can tell everything without censorship. I suppose that even then people would admire me if I said nothing of my experiences. I know that often those who do the least in a war always have the biggest tale to tell. I’m just made that way that anything exciting that happens to me I feel I must tell.

Although I have been through more dangerous and exciting things since, my first night on Normandy coast will live forever in my memory.

Imagine the difference from a heavy air raid in civvy street, vs the fact of being on a truck load of ammunition on the lift on an LCT (landing craft tank in civvy language), waiting to run down a ramp into the shallow sea leading to a hostile continent and watching through the square aperture – which made me think of a cinema screen - while myriads of ack-ack rockets gave a colossal November Fifth aspect to it all.

Out there, somewhere in the mysterious background, the sound of vehicles stuck in the soft sand and their crews shouting to the Scamel truck to haul them out, could be heard above the din of naval guns and the noise made by tanks also disembarking.

I did not know whether I would prefer to stay on board the craft, which in spite of its smoke screen was a sitting target, or follow the stream of vehicles pushing up the beach, which was an equally easy target.

That night was the first night I have really prayed in earnest, and as I offered my silent prayer an order rang out and we started to move away from the gallant, quiet naval men to whom this was a quiet night.

Down the ramp we rushed and landed with a bang in a big hollow from which our three-tonner refused to budge. Two white-faced officers appeared with a tiny torch and, seeing our predicament, told me to disembark.

I jumped from the back of the truck and landed with a splash in water and soft sand. After the Scamel had got us out, we dashed on a few yards only to sink again. Bombs were dropping in the background. I learned afterwards that we were the last truck to land that night. The Navy had decided it was too dangerous and pulled back to sea until next day.

When we finally pulled off the beach with no one to follow – the others had no need to wait – I wondered how far the enemy were from us. I believe they were about 25 miles away but of course did not have any idea then.

Our instructions were to go straight on. If we had it might have been a different story. Something made Baker, the driver, turn right. Just as we turned the corner an ADR appeared and said he was glad we did not go straight on as he was there to warn people not to because the road was mined. Of course we dared not use lights, and he had not seen us.

Fortunately, at this point, we met the RSM. who said: “Bed down for the night here because we will never find the unit in this.” It was raining heavily and the air raid continued with increasing fury. It was there that I copied the RSM’s instinctive action and dived under a truck for protection from shrapnel for the first time in my life, although by a long way not the last.

I awoke at first light, full of wonder as to how I had ever slept and shivering with cold and wet. After a tour up to the first line and all over the little bit of ground then held by the second, we found Black Jack and the blunt end. It wasn’t until about a week later that I saw the first hostile shell land two fields away, although of course I had heard plenty, even in the first few days.

At our first leaguer I was with the sharp end, though of course it was not very sharp then because we had not started ‘action proper’. However, in these early days after our landing we were open to air attack and consequently the first thing we did was to build a slit trench with sand bags on the top.

We only had it for about two days as we had to move just up the road to the blunt end. It was here that the rookies to action such as myself first realised with a shock how much a barrage fired by our own guns dug in the next field can shake you by the tremendous volume of sound. The suddenness of big guns breaking the silence and the blast which shakes leaves off trees nearly knocks one off one’s feet.

One day soon after we had settled in and Taffy and myself had built a bivvy in the safest place, a battery of 25 pounders arrived to share our field. Imagine being fast asleep in the morning to be awakened by the noise and blast of a 25 pounder! The projectile must have passed over us at about 15 feet from the ground.

This was not the worst of it, as we were soon to learn. On about the fifth day after the Huns arrived, Jerry got angry and started chucking some back. This was the first time I actually saw them landing, and incidentally about the same time I saw my first ‘brew up’ (a vehicle hit by shellfire and set on fire). I should have said my first brew up since I left England, as, of course, one of our tanks brewed up ‘on the scheme’.

Fortunately, our guns pulled out soon after this and everything ran pretty smoothly except for an occasional bit of excitement at such times as one of our bombers was shot down and the crew baled out, landing quite close to our field.

Sometimes an enemy plane would be spotted and every part of every field for miles around would spring to life sprouting small arms. The noise was somewhat like a tinbashers’ section in a factory, only on a very much larger scale.

It was like this up until about the first of July, when we had orders to pack up and make our first move as the fighting elements had made an advance. I cannot recall the name of the nearest village to the place where we moved to, but it must have been somewhere between the coast and Bretteville. Anyhow, it turned out to be a wide open space crammed with vehicles, and struck me as being a veritable death trap, especially from the air.

As it happened, we did not spend the night there for we were next on the list to go to the sharp end, which was now leaguered up about 1,000 yards from the battle. As we ploughed along the cart tracks in our small convoy, I was feeling very tense and ready to don my battle bowler any minute.

We seemed to go miles, every few yards seeming much nearer to the battle and the inferno of noise increasing, while on the other side of the road, streaming back to the blunt end, were scores of ambulances with their great red crosses looking as though they were painted with life blood.

Presently we came to a forward dressing station where stretchers were coming and going in an almost continuous stream from ambulances to marquees. Tanks, bren carriers, scout cars and vehicles of every description were ploughing backwards and forwards with white-faced squaddies in battle bowlers all alert and with guns at the ready.

At last, as darkness fell, we reached out destination. Taff’s truck was to stop in leaguer that night, but I had to go on to another to help a chap take up the ammo to the fighting vehicles.

That night was a nightmare to me, and even now I cannot recall clearly what happened. We drove over a lot of rough country without any lights at all, and at one time were lost in what was more or less ‘no man’s land’, but eventually we got our job finished and I got into bed about three the next morning. One of our lads was sniped that night and died almost immediately.

About eight o’ clock the next morning we moved again to a pretty open field from where we were surrounded almost entirely by the enemy and shells were coming in from almost every direction. We could see infantry about 200 yards away crouching behind ruins and bushes and small arms kept firing.

After a futile attempt to make up for lost sleep, which was futile as it began to rain and in any case the noise of the shells of both sides whining and exploding made sleep practically impossible, I was detailed with three others to dig a trench for sheltering casualties who were coming in fast.

We had not started digging long before two of the chaps suddenly went flat, and being more or less a rookie myself I wondered whether to follow suit but could not hear anything exceptionally close. The next minute I heard a little staccato bang and a tiny whine, I was down in a flash, and not an instant too soon, as something pinged up against the armour plating of the first aid half-truck an arm’s length behind us.

After this we took it in turns; two working and two listening under cover, but not for long as lunch was up. Meanwhile the battle around was increasing in fury and it was just as I had finished my meal that the climax came. I saw the hands of the officer in charge go up and give the signal known to the experienced as “pick ‘em”.

Simultaneously everything seemed to spring to life and move. One moment the field had the usual circus ground appearance, with brew cans, petrol tins, personal belongings and rabbits, dogs, etc strewn all over the place, the next minute everything was mobile with people running behind throwing odds and ends on before jumping in just in time themselves.

Quite a bit must have been left behind. Personally, I seemed to sprout wings and simply flew across the field, jumping into my seat beside Taffy as the truck moved. He must have been glad to see me as he could not very well leave me, but everyone guessed the seriousness of the situation and that this was what is called a ‘big flap’, and he naturally had no wish to be left behind.

Everything swarmed towards the little road gathering speed like a huge race but within an instant the road was choc-a-bloc and everyone had to slow up. This was a sniper’s paradise and shots rang out from several directions while the enemy began ranging with his big guns.

Shouts of “Get mobile for G’s sake” and plenty of foul language echoed up and down the disorderly lines of varied vehicles and here and there a vehicle bumped in front. I might as well admit that if I looked anything like I felt, my hair must have been standing vertically and my knees were in danger of dislocating one another by their knocking together, but I know I was not alone by a long way.

Once I glanced back and a petrol wagon about five vehicles behind us had been hit and was blazing. Taffy was bent over the wheel juggling and fighting for every inch of space, oblivious to my words of encouragement, and then somehow we managed to squeeze through a space and join a column that was moving.

Here a tank had driven through a wall and made a gap through which we fought our way. Many a vehicle left a mudguard or lamp behind, and any stragglers just jumped on to the nearest vehicle.

After a while our column seemed to be leaving a lot behind, when suddenly, a DR appeared, coming the other way, and halted us. We were on the road to Caen, which in those days was in enemy hands.

By this time an NCO had taken charge and calmed things down a bit by directing the column to turn round and allowing such things as ambulances through first while second drivers covered the road with stens. We were surrounded this time and the only thing to do was to find a field and leaguer up for the night.

That is how we came upon what was afterwards named by as ‘Moaning Minnie valley’. Incidentally, when we parked in this valley we made our first acquaintance with two dead cows and their subsequent odour.

Of course, we had not been there long before Moaning Minnie, or the sobbing sisters as some would call them, introduced themselves. These moaners are mortars of an automatic type exclusively of Nazi manufacture and, close up, resemble a giant revolver. The well-known noise starts with what we call winking them up, a sort of colossal rumble, followed by a long drawn out scream like a siren from each shell.

About eight follow each other at intervals of one second between each so that as the first one increases to a crescendo and explodes with a crash you can still hear the other seven screams in varying stages.

As usual there was plenty of rain about and the ground was sopping wet. This was hardly noticed, though, until during an interval we picked ourselves up from under the trucks and from the ditches to get a brew on.

Just as we had the tea in our hands, the moaning commenced again; the winding up had been drowned by other artillery fire and everyone dived again, tea flying in all directions.

After a very trying and sleepless night it was with mixed feelings that we started up at three in the morning and pulled out of the valley in the pitch dark. Many of us wondered whether those in charge knew where we were going but, fortunately as it turned out, they did.

We drove on until about ten and I was surprised that after travelling for that amount of time we were still being shelled. Along the road the poor infantry lads were plodding, some of whom had had no sleep or food for days, and it was then I realised how they were even worse off than ourselves.

Eventually we were going to leaguer on a hill top but before we could even get the camouflage nets on, the guns from the aerodrome at Capriquet opened up, getting our range almost immediately. I saw the first two land in between vehicles and, deciding that the next would be very close, I went flat just in time.

Looking round I saw a chap, further away from where it burst than I was, crumple up and scream with the agony of the shrapnel in his body.

Just then the “pick’em” signal was given again, but this time there was only our own mob and one other, so things were much more orderly and we just raced round the corner to a field below the ridge where we could not be observed except from the air.

Two of our cooks were injured in this ‘do’. We found some very elaborate slit trenches which had been dug by Jerry in this field, and in one corner was a stack of about 500 bikes.

We stayed there for about 36 hours and felt comparatively safe after watching the shells for a while and noting how they only landed just on top of the ridge. This action was called Hill number something and I expect it was mentioned in the news.

When we moved again from this place, we guessed we had to run the gauntlet of the Capriquet guns again, and as it happened just as we got to the corner approaching the topmost part of the ridge we were held up while the fighting vehicles passed.

As we waited by the roadside dismounted, one shell screamed extra near and I dived into a convenient slit trench as it landed very close, followed by another and then another.

Peeping up as the last one fell, I saw it hit the front wheel of a jeep about four vehicles in front of us, and huge boulders became airborne. Then we were off again, dodging the holes and pushing on down the road while they landed each side of us.

In a few minutes (it seemed like hours), we turned another corner and were more or less out of sight. Finally we leaguered up at Bretteville where the enemy was a bit quieter. But we had an enormous amount of big guns which, incidentally, fired the biggest barrage of the European war up until then.

It was there that tiredness overcame everything and I slept through noise enough to waken the dead. Soon after this, about July 14th, I went back to the blunt end which had moved back to its original place where we started. That brought us near to the close of the Caen sector and the start of a new push.

It started after several days of rest at a place the name of which I never discovered. We had passed through a village previous to the resting place and we were not so far from France proper. This we could have guessed without the aid of the map as the village gave us a good cheery welcome.

At the resting place we revelled in the luxury of a real mobile bath, our first in fact. There was also a cinema and ENSA show. I was with the blunt end at the time and, incidentally, attended, for what was to be the last time, Sunday service given by our late padre.

The next afternoon we were warned to be ready to move and lined up ready for an early start. I happened to be sleeping under Skilly’s truck when I was awakened by the noise of explosions and, as we were a good way behind the line, wondered what was happening.

A few minutes later our sergeant appeared in his pants and hurriedly but calmly told all the ammo trucks to move to the other side of the field. When I emerged from the truck I was dazzled by the fire which came from the turret of a tank standing on the opposite side of the road. Skilly was up in an instant, as were the other drivers, and we just pulled away in time as the AP Negam ammo began shooting out in all directions; some of the tracer small arms ammunition could be seen clearly passing over where we had been parked five minutes before.

We soon got to sleep again, and when we left in the morning at about six the tank was still smouldering.

It must have been on the night following this incident that, after parking for a while at a field some miles further on, we had to move again. It was one of the worst possible nights for moving as the darkness was impenetrable and a mist of rain made visibility along the narrow winding track almost nil.

Each side of the truck sloped sharply down to a deep ditch and there were murmurs of discontent from the drivers as the long column snaked its way slowly out on to the track. Use of lights was forbidden as it was necessary for the movement to be as secret as possible.

Hardly ten minutes of driving had elapsed before there was a sudden halt. Engines were turned off and we heard shouts further down the line, followed by a hail from an NCO. Stumbling down the road we found illuminated help, but there were already enough men formed in a chain throwing the shells frantically out of the back of the truck.

Very soon one man was brought out on a stretcher, followed by a little dog. The dog was uninjured but the next lad they brought out was contorted in a bent position. When they laid him out on the stretcher it was clear that he had been crushed to death. The driver was alright and the other chap in front was only suffering from shock.

Geordie and I were told to bring our truck up and the victims on the stretchers were lifted gently in. Then began a nightmare journey through the blackness, with two other lads and myself holding the stretchers on the back.

Once we narrowly missed going over ourselves, and just as we got nearly to the ADS (advanced dressing station) we did get stuck in a ditch. Luckily an ambulance soon appeared and the victims were transferred, after which we dug ourselves out and pulled round the corner into a track which was not used much. We just threw our blankets down and slept.

The next morning, we went to the ADS to see how our comrades fared and I saw for the second time the face of the unfortunate lad who had met his end the night before. He looked very peaceful and dignified lying there covered with blankets, and I pulled one over his head, which was hardly disfigured at all apart from a slight blackening of the eyes and a trickle of blood from the mouth.

I have thought about this accident several times since then, as the truck that was involved was Taffy’s. A fortnight before I had been living on that truck and when Taffy managed to get his best pal on with him, they had both said to me: “You can stay on if you don’t mind riding in the back.”

The next day the Battle of Falaise was in full swing and we moved up again. It was during this time that I entered for the first time a cottage which had been evacuated and looted more than once by the Boche.

Everything seemed to be sleeping in this ravaged little home and I felt like talking in whispers. A nauseating odour pervaded our nostrils and as we climbed the stairs it grew in intensity to a degree which would have brought up the gorge of a weak-stomached person.

In a little room on the left was a most gruesome sight. What had been a large dog lay under a seething mass of maggots, the skull and the teeth being the only evidence of its origination. I was glad to sample the fresh air again and walked through the orchard to the field, where some of our lads had succeeded, after a hard struggle, in capturing a cow that was in great pain and were relieving the beast by milking it into the ground. The milk is no good when a cow has reached that stage, but I think these cows will have made a recovery.

Further on was the house of some well-to-do person, probably the mayor. It had been a beautiful home before evacuation, but some maniacs had smashed everything, even to the large mirror and the kiddies’ little dolls and playthings. This is not propaganda. I saw it and pinched myself to be sure I was not dreaming.

That afternoon some of the evacuees began to return, pushing prams with pathetic little kiddies sitting on top of the equally pathetic bundles of what was left of their little belongings. We thought of what they had yet to go through when they discovered the rape of their cottages.

With the first light we moved again and the colourful dawn on this occasion is still in my memory as a contrast between nature and the filthy destruction wrought by man. That dawn was the only beautiful sight we saw that day, for as we advanced, we came upon more scenes of death and destruction.

Hardly had we reached the next leaguer and filled up with petrol before I was detailed with five others to proceed to the sharp end for a prisoner-of-war guard. As everything was on the move, it was difficult to find our forward echelon (soft vehicles, lorries and supply vehicles) and so we stopped in the main square at Fleurs to enquire about which road to take.

This town bore the scars of modern war and many shops had been looted. It was almost deserted and once again one felt like talking in whispers.

When we moved on again, we began to pass wrecks of vehicles, mostly of the horse-drawn type, and the overpowering stench of dead cattle was indescribable. Scores of what had been beautiful horses lay in a variety of positions on the side of the road, some without heads, others with no visible sign of the cause of their death. Most of them had been used by the enemy for military purposes but some had belonged to civilians; refugees’ belongings were strewn across the road.

Here and there were the bodies of the retreating army, their field grey splashed with mud and life blood. There was no time for Christian burials that week. All the time we were overtaking vehicles and even tanks until finally we saw the familiar sign of our sergeant in charge of the sharp end. There he sat in his jeep looking like Monty himself, a smile on his war-lined face.

Now we were very close to the Falaise Gap itself, the hole in the colossal pocket through which thousands of Germans hoped to escape. A roar of engines sounded above the sound of the traffic and we looked up at the familiar sight of spitfires coming in for a kill.

This time, however, we felt a little worried and I remember remarking to my comrade: “I hope the RAF has heard the one o’ clock news and know how far we have advanced.”

They had, and I witnessed one of the most thrilling and exhilarating sights I had seen so far, as one by one they peeled off and dived. It was then that I realised how close the enemy were.

I could see plainly each bomb as it left the ‘plane and I followed with my eyes the descent until, just for a fraction of a second, the missile was too low for us to see and then the climax as ‘whoop’, up went a cloud of dust and debris followed often by an outbreak of fire. Here was proof of the accuracy of our courageous air force.

A few minutes later the column was held up and we had a chat to some lads in a bren carrier. It was probably their last little chat, for five minutes later we moved on a couple of hundred yards past them and heard that well known thud and shriek. Looking back, we saw the first shell land just off the road. The next exploded with a crash, plump in the middle of the road… where we had been before. A tell-tale cloud of smoke and flame gave evidence that Jerry had scored a bull’s eye.

Imagine my relief when, after the third shell had landed, the column began to crawl on again and very soon we pulled off the road to halt for a meal. The tanks, in the meantime, were taking up positions behind haystacks ready to deal with the cause of the trouble on the road and soon their big guns were bashing back at the hidden enemy.

We ate a good meal and exchanged tales with our mates. Soon we were on our way back to the blunt end and our driver must have known what I was thinking. He stepped on the gas. As we passed the scene of the shelling, we had to swerve around the blackened remains of the petrol truck and bren carrier.

The blunt end had moved, and after trying for hours to find them we packed up for the night outside a cottage and made our beds in the front garden. Next morning we found the blunt end and moved with them to Agentan.

It was at this time that the sergeant major, whilst out on his own apart from two clerks, took the wrong road and was captured by a few Jerries in a tank. After spending two days with them during which the tank ran over a mine and one of the clerks got both legs broken, they (the Jerries) decided to give themselves up and Black Jack, as we called him, brought them in.

A few days after we reached Argentan with the blunt end, the real push, which was to take us to Belgium was to begin, but we had no idea as early as that.

At this point in my memoirs, I become extremely hazy as to the sequence of events and places. However, the place I remember as being more or less the starting point and where we got the first rumour that the chase was beginning, was a small town named Etrepagny, in which we arrived about ten am one August morning after travelling all night.

This was the blunt end, and our lot had to pull off the road to let through a stream of utmost priority vehicles. Officially we were confined to the field ready to start up at a moment’s notice directly a gap appeared in the traffic.

We washed and shaved, made our respective brews and argued with each other on the risk of walking a couple of hundred yards into the centre of the town. Finally, some of the “barbary crowd’, including yours truly, set off with stens and a magazine each. This was a necessary precaution as the town had only been in our hands a few hours.

When we arrived at the town hall we found a large crowd was collecting ready for a ceremony of clipping the hair of female collaborators. There was much excitement, with kissing and handshakes and cigarettes for poppa. I met two college girls and their mistress, all of whom were anxious for souvenirs, and divisional signs were fast disappearing from the shoulders of the liberation army to appear, very likely, the next day on the coats of liberated females.

Just as I was doing well with the co-eds, there was a flap started by a false alarm rumour that we were moving, and everyone started back towards the leaguer. DRs were sent around to collect all the wandering drivers, and they soon returned. It was, as usual, unnecessary, as we did not move until about six.

I think we leaguered the next morning somewhere near Amiens, while the sharp end had spent a glorious night there. By this time, we were getting excited, Jerry was certainly on the run and there was no knowing where he would stop.

The tanks were using much more petrol than ammo and it was the crucial part of the chase, perhaps the most essential thing at that time being that petrol must reach them somehow.

A tank will only go as far as its fuel will take it and then it must refuel. That is, of course, common sense, but the complicated system needed, and the hard work attached to that carrying of fuel from the landing stages right up to the tanks in time before they run out of juice, is something not realised by the average civilian.

Geordie and I were changed from ammo packet to petrol, which meant that we had to get a quick meal directly the blunt end leaguered and dash back to RASC, where we dumped our ammo and filled up with a load of petrol.

Returning. we found the boys on the move again and were able to pick up our position in the column as it was not very fast moving, owing to the fact that there was such a large amount of stuff going up.

We began to meet more Maquis with their tricolour armbands and gave some a lift. We kept going well into the night and when the blunt leaguered for a meal about twelve we had to get ours and hurry off to join the sharp end at about four in the morning on what must have been about the last day in August.

We snatched two hours sleep, had breakfast and a quick wash, then got on the road at 6.30 am. The advance was going at such a speed now that we had to follow often a few hundred yards behind the tanks and chance pockets or being cut off.

As we rumbled into [blank], pandemomium was let loose amongst the population and the sort of reception which has been filmed and talked about all over the world was showered upon us.

It was a most complex feeling that I had that morning. One of intense excitement and a feeling now, even more than before, that we were living characters in a serial story of the thriller type. Yet there was a chance that any moment we might meet a rearguard action by the enemy and be right in the middle of a fierce battle.

There was a flap when we were in [blank] and I have described how the French, although naturally frightened, behaved very well. The tanks opened fire and the noise was terrific, but it was soon over and another batch of prisoners brought in.

We moved on again, and as we drew away from the town the atmosphere became tense again. My heart was in my mouth on two or three occasions that afternoon. First when an armour piercing shell hit the ground within 15 yards of our truck and ricocheted over the top, barely missing the canvass, and again when a ‘laughing gun’ opened up nearby.

Presently we crossed country by a rough path and this seemed to me to be an obvious sign that Jerry was somewhere on the road and we were bypassing him. Then we got back onto the road again and passed through another town, where we were pelted with boxes of cigars which were made for Wermach.

We leaguered for the night close by a village where some others and myself visited a family and talked with them in what French we knew, helped by a little English that they had picked up, such things as the “robot” flying bomb.

We were going out in the evening, but a flap started, people began pulling down flags and the tanks went out to investigate a large pocket which was supposed to be moving towards us. We loaded our guns and stood by for about half an hour. When nothing happened we got ‘cheesed off’ and a NAFFI van arrived, making everyone forget the danger which threatened. It started to pour with rain and an hour later some of the tanks came back reporting everything under control. Soon the flags went up again.

The following day we were going again and beginning to wonder whether we would find that someone had dropped a brick and suddenly be surrounded. All day we were cheered and the truck now covered with slogans - “Vive le Tommy” etc. What with this and the fresh flowers which were allowed to drop off directly they drooped and be replaced by the almost fanatical crowds at the next village or town, the whole column had the look of a grand carnival.

The boys were very excited by now and nearly everyone had drunk a good amount of alcohol except the drivers.

Although so much temptation was thrown in their path in the way of wine, women and song, and it would have been easy to get left behind unnoticed, to my knowledge every man did his best to keep up with the column. Everything depended on the supplies.

Towards the evening, I felt like the King must feel after a hard day acknowledging applause. The thing began to get even a little monotonous. A civilian car which had been appropriated by the French Forces of the Interior and had the initials painted on with the Croix de Lorraine, was wedged in behind us. The occupants, four young, neatly dressed

gentlemen, seemed most indignant at the way people included them in the welcome by throwing posies and bottles to them.

I was speeding up and manouvering until they managed to get alongside, with one man hanging out, his arm outstretched, holding two bottles. A little spurt of speed, a quick grab and I had added two more to the collection. This went on for a considerable time and I had bottles of beer left for about a fortnight after this.

It was dark by the time we crossed the border near Lille, and soon after the tanks stopped and we refuelled them on the road. Halfway through this operation, heavy explosions broke out nearby and a corporal appeared, urging us to hurry as there was trouble.

The trouble sounded very close and I gave the cans an extra bang so that I should not hear what was going on as my nerves were a bit overstrained.

At last we finished and got all the empties possible on, but we were instructed to park on the edge of the road and dismount with our stens and take up positions in the ditch, which skirted the road.

Several tanks could be seen brewing up and an attack of some kind was being made by enemy infantry. We were ready to shoot at the slightest suspicion, and the way my hand shook it’s a wonder I did not shoot my comrades. However, after about an hour, which seemed like ten years to me, we pulled off again and kept going until four the next morning.

Geordie and I had two hours sleep, until six, when we had to go back to the blunt end and from there to the RASC to fill up, then back to the blunt end again.

We were now in Belgium, and on the second morning after crossing the border, September 4th or 5th, we attended a welcome parade given by the Bergermeister and several hundred school children, an hour after which we moved along a great road reminding me of the great west road, and reached Hemisken in the late afternoon.

The tanks were now in Antwerp and we were all to have five days rest.

Tony Jones reflects on the life of his father, Waler Pettinghill Jones

My father was born in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk on 31 May, 1915, the second of two brothers, and was educated in the town’s grammar school. He married Ann Paulina Lindsay in September 1938.

Walter joined the Royal Engineers and rose to the rank of Corporal. He was commissioned into the Dorset Regiment as a Second Lieutenant some time in 1943 but achieved a third pip before demob.

Having completed officer training at Barmouth in North Wales my father was commissioned into The Dorsetshire Regiment with which, as a Norfolk lad, he had no real links.

At Normandy his unit went ashore at Arromanches, I believe quite some time after 6 June, but I know little of the detail until he was seriously wounded on the gradual slopes of Hill 112 on 14 July.

Blessedly, and thanks to a string of providential events, he survived the mortar/shrapnel to the back of his right lung which created a wound big enough for a child’s fist to enter. My father would have been in command of a platoon and he credits Platoon Sergeant Perry with getting him back to safer conditions and thus saving his life.

Walter also praised the Canadian field hospital for not ‘writing him off’ and was grateful for the low-level air-evacuation to England, where most of the repair work was done at Weston-Super-Mare aided by the early hit-and-miss use of penicillin. He also developed a new-found taste for the body-building properties of Guinness.

My father recalls that Sgt Perry (possibly John Perry) then took command of the platoon but was killed in action the very next day. As a newly-joined member of the Aldershot Branch of the ‘Normandy Vets’ in 1994 my parents found their way to Perry’s headstone at Bayreuth War Cemetery. I think my father once mentioned that he had visited Perry’s widow but I am not quite sure of that nor know any details.

I was with my father on his visit to Bayreuth and joined him on a trip to Hill 112. He had no problem recognising it, although the first thing he said was: “… but of course it was in mid-July, not early June as it is now, and the corn was high and almost ripe not short like it is now”.

He mentioned the Germans being mostly in the dead-ground behind the hill, and remembered their loudspeakers blasting out dire warnings of the death trap prospects and the leaflets dropped containing the same message. Waler also spotted the small, barn-like structure down to our left which he noted looked much the same as it had 50 years prior.

He had a diamond in a gold ring and, if prompted, could point to a small piece missing from the stone, supposedly chipped off when handling a busy bren-gun.

At the top of what should have been that insignificant hill where roads meet in a Y-shape and where now stands a modest marker recognising the presence there of the Wessex Division, we took obligatory photos and then, in my father’s words, needed to “get back to the trucks!” He meant, of course, the waiting luxury French-registered tour buses, but with a give-away slip of the tongue, he had turned the clock back 50 years.

Not all of my father’s war-time recollections over the years were positive, and he felt he had witnessed unwarranted and wasteful loss of life. On this powerful Memory Lane visit we happened across what, if I recall correctly, was some sort of chapel in woodland around which he relived the disarray of the dead and dying and the digging of temporary graves - perhaps his only real reference to the horrors of war.

Before the war was over Walter was back in uniform and based at Hythe, Kent, as a weapons-training officer where an ammo malfunction occurred for which he was suspended, awaiting possible court-martial.

Consequently, my father’s wartime recollections were to be muted and qualified and he did not claim his service medals till many, many years later, when perhaps an old man’s moods have mellowed. Nor did he seek pension/compensation for war-wounds until the Royal British Legion “put him up to it” years later. As a result he was awarded 100% war disability allowance, which he accepted but actually thought was “a bit Ridiculous”.

Having myself just missed out on National Service in the very early sixties, I applied instead for officer cadet training with a view to a three year Short Service Commission which, at Her Majesty’s Command, I received into a reputed County Regiment. At the time, my battalion was stationed at Shorncliffe, and my dad accepted the colonel’s invitation to a really rather magnificent mess night.

I was walking my dad back to his room - me in rather pompous scarlet mess kit and my father in simple ‘black tie’ dinner jacket. Out of the blue from out of the silence between us he turned to me and said: “You know Anthony, at least you are part of a proper Army.” I couldn’t believe my ears – It was the stupidest thing I ever heard him say.

Walter fathered three sons and had a very full, mostly happy life, working until the age of 68 and dying in Hampshire aged 89.

Anita Penny looks back on her father’s wartime experiences in the front line

Thomas Henry George Penny was born 1920 on, of all days, 11 Nov. He joined the Devons and Dorsets, was called up and landed on Gold Beach on D-Day plus a couple of days. We often see him on television in The World at War and more recently in videos commemorating D-Day.

Like many others, my father didn’t talk much about the war, but as he got older and I grew up, I would ask him about it and he told me bits. I know he was buried alive twice and was saved once when someone saw his foot moving. On another occasion he woke up in a Canadian field hospital. Both times he recovered and carried on fighting.

Thomas fought under Monty in the battle for Caen and Hill112. His best mate was blown to pieces alongside him, and thats when he would say no more. He did, though, tell more light hearted stories, including how he dropped his tinned peach rations in a trench but had to wash them off and eat them rather than go hungry.

I think dad’s regiment was called The Wessex as they joined with Devon. His cap badge was Dorchester castle. He was a medic and a sniper and he also played in the Army band.

After he came home at the end of the war he suffered greatly with noises and explosions in his head, known today of course as post traumatic stress disorder but back then as ‘shell shock’.

He was a country lad, so many of his mates had been exempt from joining up so they could work the land, and they used to tease him and call him all sorts of names. He had a bit of a short temper for a while, and they would goad him to make him snap. They didn’t have a clue what he had been through. Those were hard times, but he met my mum a few years later and things got better.

I would attend Armistice Day and stand by the war memorial at our church with him every year. His friend’s name was on that memorial. I will never forget his name - Charlie Neave. My dad also tested various gasses at Porton Down, volunteering for an extra two shillings a time.

He tested some nasty stuff. He would go into a room with, as he called them, “the boffins”, on the other side of a pane of glass, I imagine with an opening, and they would pass a canister through. Dad had to point to where on his body the gas was affecting him. He said one made his skin come up in huge blisters and another time he lost his voice. He didn’t realise at the time just how dangerous these things were.

Dad died aged 76 from lung and larynx cancer. I often wondered if those tests contributed, but we will never know. He wanted to fight for his country, and I am so proud of him.

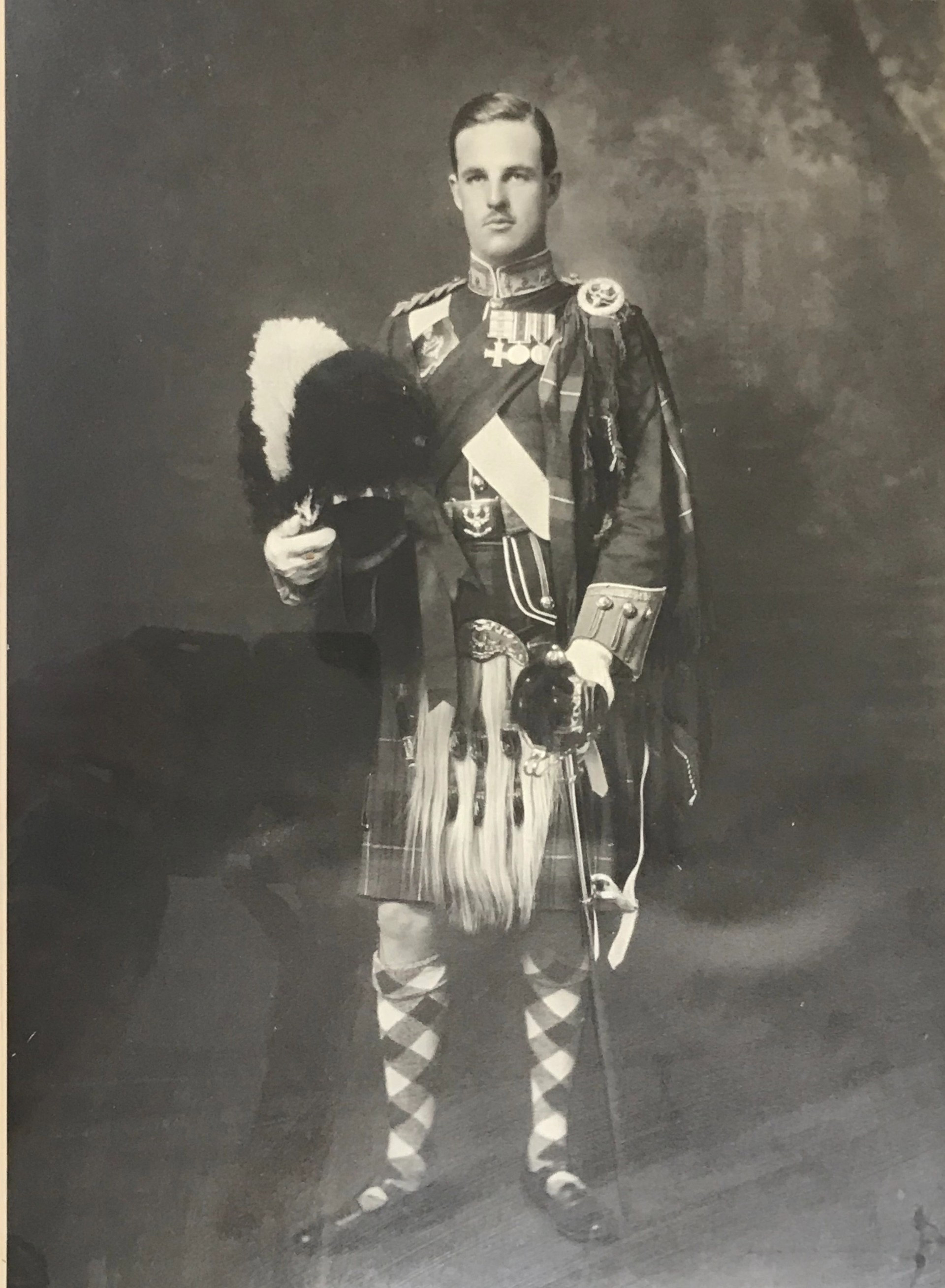

Brigadier Ronnie Mackintosh-Walker was the brigade commander of 227 Highland Brigade, part of the 15th Highland Division, and was killed at Baron-sur-Odon on 16 July 1944. He was the most senior serviceman to be killed in the whole of the Normandy Campaign.

Giles Nevill has now funded a plaque at Hill 112 in honour of his great uncle and has provided this link to a biography about this remarkable man and his gallantry.

Follow this link to find out how you can commemorate one of the heroes of Hill 112

Alan Berry recounts his father’s experiences in the summer of 1944

My father, Private Arthur Ernest Berry, wasn't included in the D-Day landings on 6 June. His battalion was part of the 129th Brigade of follow-up troops charged with reinforcing the push against the Germans once the beaches had been secured.

His 4th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry, part of the 43rd Wessex Division, embarked from Newhaven and London Docks. Dad sailed from London on Sunday 18 June and arrived in rough seas off Arromanches the following day. The Mulberry harbour wasn't yet useable, so it took days for the Wessex Division to re assemble ready to move up to the front line inland.

So it wasn't until Sunday 25 June that the battalion moved off inland to Brecy, where they bathed in the river and made ready to take over from the 15th Scottish Division, in reserve at St Manvieu, the following day.

The first casualties from shell fire occurred on 28 June Four men were killed, one aged just 19, Private V Williams. Another, Private R Ryder, was 21.

A brigade advance across the River Odon gorge was ordered for Thursday 29 June. The 5th Wiltshires were on the right, the 4th Somersets on the left and the 4th Wilts in reserve. The advance was over an area of about two miles on an axis of Cheux-Mouen-Tourville, to the west of the city of Caen.

The advancing men encountered heavy mortar fire and the tanks were unable to cross

the gorge. Seven men, including 18 year-old Private Cooksey, became the first casualties to be killed in battle. Another six were killed the following day as they tried to push forward over the Baron-Fontaine-Etoupe road which C and D companies had managed to cross.

Dad records, with some sadness, that 30 June was the day he first killed a German. The next five days were virtually a stalemate as the troops endured intense artillery fire until relieved by the 4th Wiltshires on 5 July. The Battalion withdrew half a mile and received three new officers and 62 other ranks, its first reinforcements. Four days later they were back at the front line in the positions they had left previously.

The next day, 10 July was earmarked as the day a main Brigade assault on Hill 112 was

To be made, with the battalion central to the attack.

Monday 10 July 1944. The Battle for Hill 112

The plan was for the 129th Brigade to attack Hill 112 and the 130th Brigade to attack

Maltot in the early hours of 10 July. Dad’s 4th Battalion was to be in the middle, the 5th Wiltshires on the right and the 4th Wiltshires on the left.

This was to be a three-phase attack, the initial attack to commence at 0500 with an artillery barrage along the whole front. As the advance commenced, the troops came under concentrated mortar and artillery fire, with little or no cover in the open corn fields at the bottom of the slope that led up to the ridge of Hill 112.

The Somersets encountered an array of weaponry being used against them, from small arms fire, machine gun and flame throwers to heavy mortar and tank artillery. Casualties were high, both dead and injured, with the scene being described as "hell on earth". The total of 43 dead men included two more 18 year-olds and six who were aged just 19.

Dad received shrapnel wounds to his neck, back, legs and ankle but not serious enough to take him out of the battle. As a young boy I can remember him having pieces of shrapnel that had worked their way to the surface surgically removed.

The battalion was too weak to proceed with phase two and was ordered to hold the line as much as it could. This continued for two days more, despite the Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry trying to push on through the Somerset lines.

The battle turned into an artillery slogging match, with what was left of the battalion bring withdrawn at 2300 on the 12th, but not before another 20 soldiers had died.

The battalion that had left England just weeks before was now decimated, and two

days later it received reinforcements of 394 other ranks and 12 officers to bring it back up to strength. Only 12 officers and 124 men had survived this first and bloodiest of battles, the bloodiest the Allies encountered in Normandy and certainly a baptism of fire for the young soldiers.

Dad only returned to Hill 112 once, just a month before he died, in August 1981. There was the stone monument there, but nothing else at that time. He chatted to a German chap whose father had been a soldier back in 1944 and against whom dad may have fought.

I don’t recall Dad saying much about his experiences; who knows what memories he would have had about that hill? He certainly had the nightmares and periods of depression that so many soldiers returned home with.

I have walked up the slope of the hill through the cornfields he would have crawled through with bullets, shells and bodies littering the ground. It’s hard to imagine such a scene. Eighty years on, peace restored, the hill is no longer stained with the blood of those young soldiers.

The story is shared with the kind permission of Malcolm and Cathy Colman, the niece of Ernest and Henry McDonald, the two soldiers who feature in the story. Cathy did not know much about her uncles as her mother died when she was young, but while researching the family’s history her husband Malcolm discovered their connection to the Battle of Normandy.

Ernest Frank McDonald was born near Southampton on 25 October 1916 and his brother, Henry Charles, was born on 24 June 1925. They were the sons of William McDonald and Elsie May McDonald (née Emmett).

Ernest and Frank grew up to have two contrasting service experiences.

Ernest Frank McDonald

Ernest worked as an errand boy until enlisting in the Regular Army on 25 June, 1935. He joined the Dorsetshire Regiment as Private No. 5725398.

After training, Ernest was posted to the 2nd Battalion on 12 January, 1936. He was posted to the 1st Battalion on 9 March, 1937 and served in India until 1939. The Battalion was then posted to Malta, where it manned the defences during the siege.

Once the siege was lifted in 1943, the battalion was posted to Egypt. On 29 June, 1943 the 1st Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment embarked on the SS Strathnaver, bound for Sicily and the landings on 10 July 1943. Ernest’s campaign in Sicily lasted until 5 November, 1943 after which he took part in the landings in Italy.

Ernest’s battalion left Italy and returned to the United Kingdom, arriving in Gourock on the Clyde on the evening of 4 November, 1943, to prepare for D-Day in Normandy. He had been away from the UK for eight years an 134 days. He went on leave around 7 November, 1943, re-joining shortly after for D-Day training.

The Dorsetshire, Hampshire and Devonshire regiments became part of the Northumbrian Division and trained as one. Ernest's last campaign was about to begin; his third and final landing from the 6 June, 1944 until his death four days later near Tilly-sur-Suelles in Normandy, France.

Ernest Frank McDonald was awarded the General Service Medal and Clasp Palestine, 1939-45 Star, France and Germany, Africa Star, Italy Star and Defence Medal 1939-45. He had served for a total of 8 years 352 days.

Cathy Colman at Ernest's grave, Tilly-sur-Seulles Cemetery

Henry Charles McDonald

Henry worked as a sheet metal worker and labourer. He joined the Home Guard in July 1941 before enlisting in the Territorial Army, Hampshire Regiment, General Service Corps on 8 March 1943, as Private 14425166, aged 17 years 8 months.

He was sent to the 66 Primary Training Unit on the 15th April 1943. After training Henry was assigned to the Hampshire Regiment on 27 May, 1943, but was in detention for some reason (redacted from his records) until re-joining the 7th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment on 24 March, 1944.

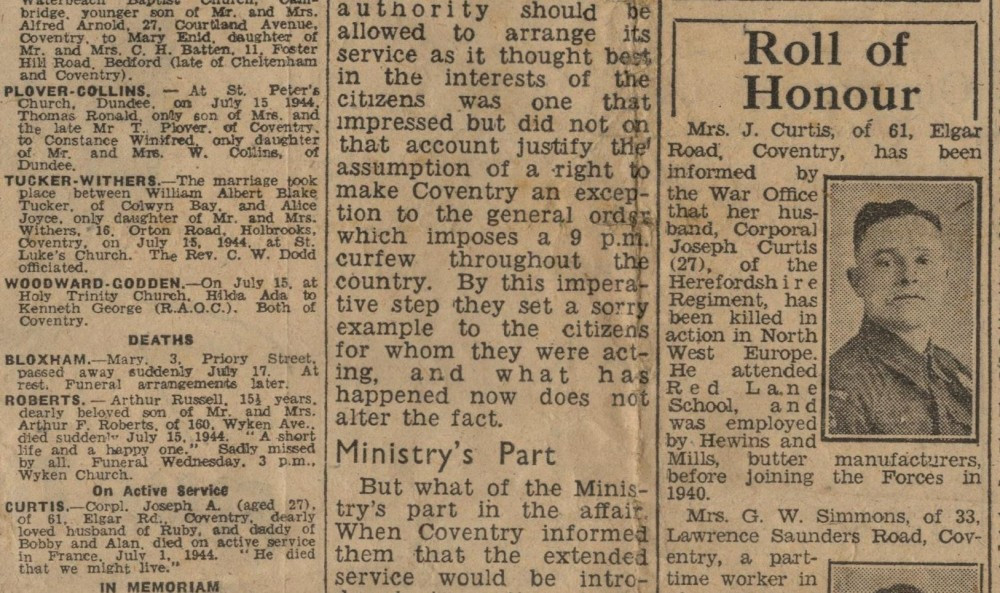

On 19 June, 1944 the 7th Battalion went to Normandy, France. Henry Charles was reported missing, killed in action, on 10 July, 1944. He was awarded the 1939-45 Star, France and Germany and War Medal 1939-45. He had served for a total of 1 year and 125 days.

Henry Charles McDonald has no known grave and nobody knows where he was killed. He is commemorated on two memorials, in Bayeux and at the British Normandy Memorial, Ver-sur-Mer France.

Malcolm Colman takes up the story:

“While visiting the British Normandy Memorial in June 2023, my wife and I were looking at the plaques on the benches that face the memorial. I was looking on the front of the benches, my wife was looking on both sides.

“I commented that one bench did not have any plaques on. She then told me there were some on the rear. I went around the back of the bench I was looking at only to find a plaque that said: ‘Remembering with Pride, 7th Battalion The Hampshire Regiment, 4th Battalion The Dorsetshire Regiment, 5th Battalion The Dorsetshire Regiment which, as 130 Brigade, attacked the eastern shoulder of Hill 112 on 10th July 1944.’

“Operation Jupiter was a fierce battle fought on 10 and 11 July, 1944. The 43rd (Wessex) Brigade, which included the three battalions named above, fought on the eastern side of Hill 112, reaching Evrecy and then Maltot on 10 July, 1944. There was fierce resistance from a battalion of Tiger tanks of the 102nd SS Panzer-Abtielung accompanied by SS Grenadiers.

“My wife and I believe Henry Charles McDonald was killed in the fight for Maltot. We have since visited Maltot (we visit Hill 112 regularly as we drive to our cottage) and now at least have an idea where Henry Charles was killed, all thanks to a small plaque on a bench at the British Normandy Memorial that I nearly missed!”

In May 1943 I joined the Essex Regimentt, aged 17-and-a-half and was posted to 2/4 Batallion. I was stationed in the Isle of Wight, North Yorkshire, including two weeks in trenches on the moors, and at Fareham. I aualified as an Infantry Signaller.

In April 1944 I was one of a party of 200 transferred, the 4th Dorsets in Bexhill and in June of that year I boarded MV Pampas in Southampton, landing on Juno Beach on 23 June.

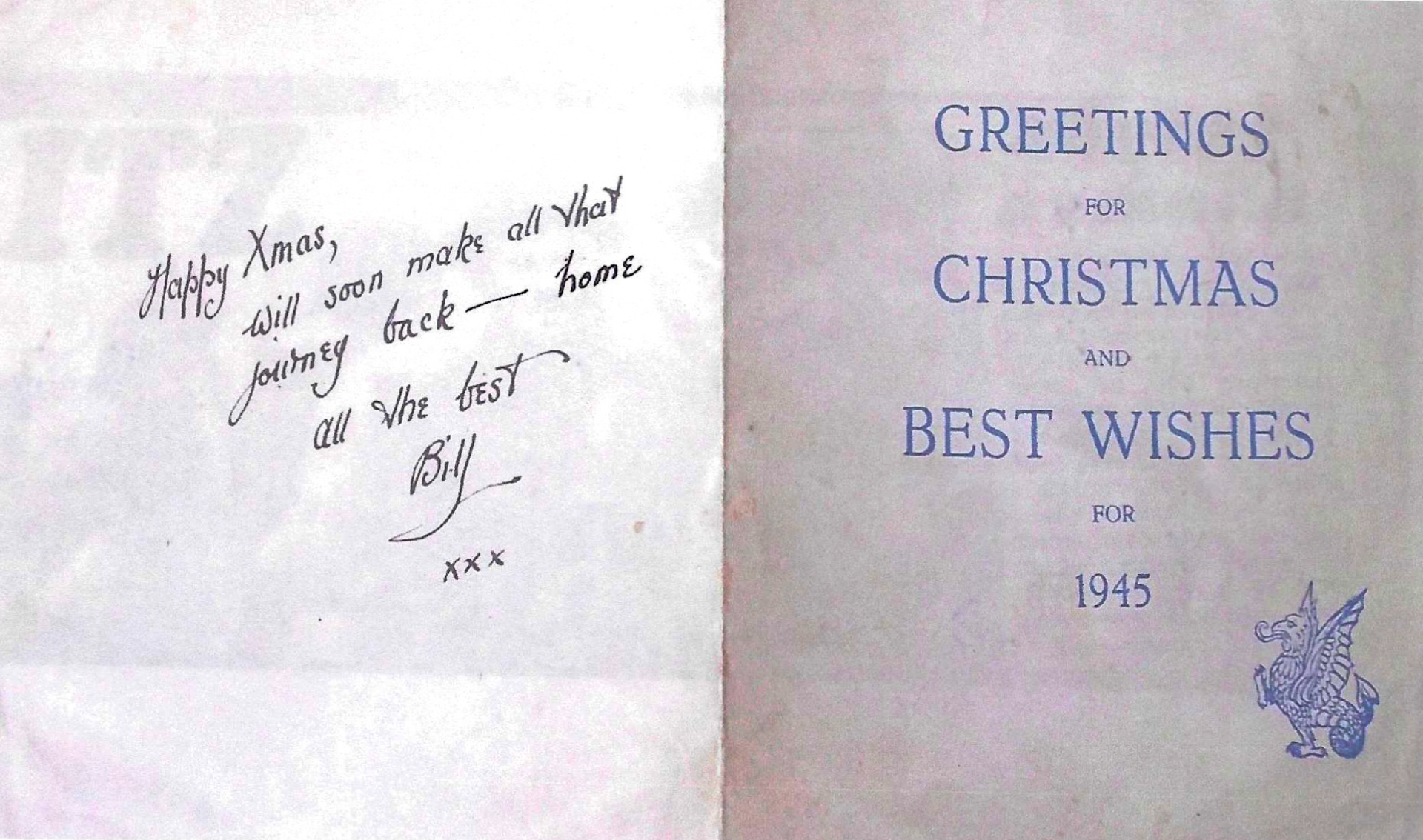

Overnight on July 7/8 I was one of 30 men on a platoon night patrol behind German lines when we were cut off, and battle ensued. Sixteen men, including my brother Bill, got back, five of us were captured and we presume the other nine were killed in action.

We were transported via Falaise and Alencon to Chartres before enduring two horrible train journeys which involved 40 men in each wagon with a lidded dustbin as a toilet. The first journey took six-and-a-half days and took us from Chartres to Aix-la-Chapelle (now Aachen) and the second saw us travel from Aachen to Cieszyn in southern Poland - Stalag VIIIB Teschen, to be precise - in just under six days.

After a week we were taken by lorry to Gliwice them marched to Zabrze (north west of Katowice) and put to forced labour in a coal mine. I was mostly on the 6am to 2pm coal-cutting shift (two prisoners and a miner to each face), but I did one week on nights, blasting down rock to back fill the shaft as it was moved through the earth.

On 20 January, 1945 we went down as usual but the miners were not there, having been taken to join the Volkstumm (Home Guard) to help repel the Russian advance. We refused to operate the mine just with German foremen so they left us down there for our eight hour ‘shift’.

The same thing happened on 21 Jan, but on the 22nd we stayed in camp and were then. told that we were being moved to a new camp the next day.

We set out in bitter weather, marching all day and night through snow and ice on what later became known as The Long March to Freedom, heading southwest through the Czech border and on to Pardubice.

Spring arrived to melt the snow, but we turned north through Jungbunzlau (now Hradec Kralove) to meet snow again en route to Liberec, then west into southern Germany (below Dresden) and south to Bavaria.

We reached Michelsneufkirchen in a forest east of Regensburg on 20 April, when we heard gunfire from the west at night and refused to march any further as liberation was near. Two American tanks arrived at our farm on Sunday 22 April to take out guards prisoner.

We were flown from by Dakotas to Reims (Theatre of Arts), east of Paris, where all our clothing was burnt as we had slept in barns and become lice-ridden. We enjoyed a hot shower, were kitted out as Yanks and were flown by Lancaster to Dunsfold on 4 May 1945.

The American kit was exchanged for British kit and on Sunday 6 May I took a train to London and then home to Barking.

Postscript

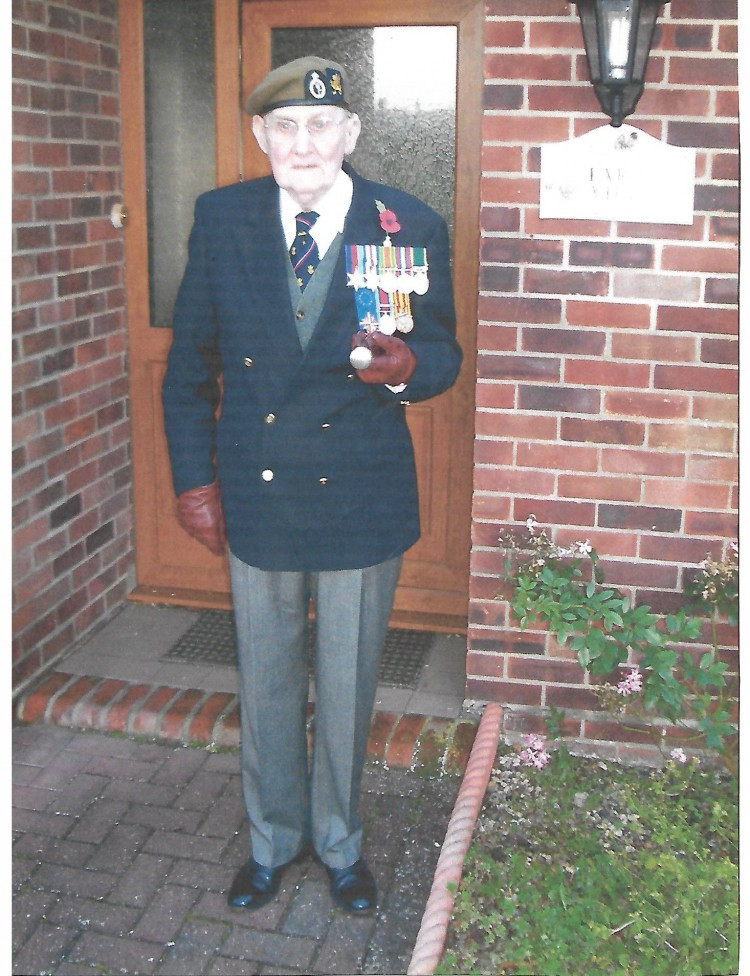

I had entertained hopes of being demobilised, but the forces’ method of discharge was based on age and length of service. As I was still only 19, I was transferred to the Royal Corps of Signals and posted for two years in Catterick.

I qualified as an Operator Wireless & Line (OWL) but transferred to administration and became Corporal i/c Records of a large training regiment (1 Trades). I was transferred to Class Z Reserve on 12 July 1947, on which date I collected my civvy suit and returned home. I was released from the reserve in January 1948.

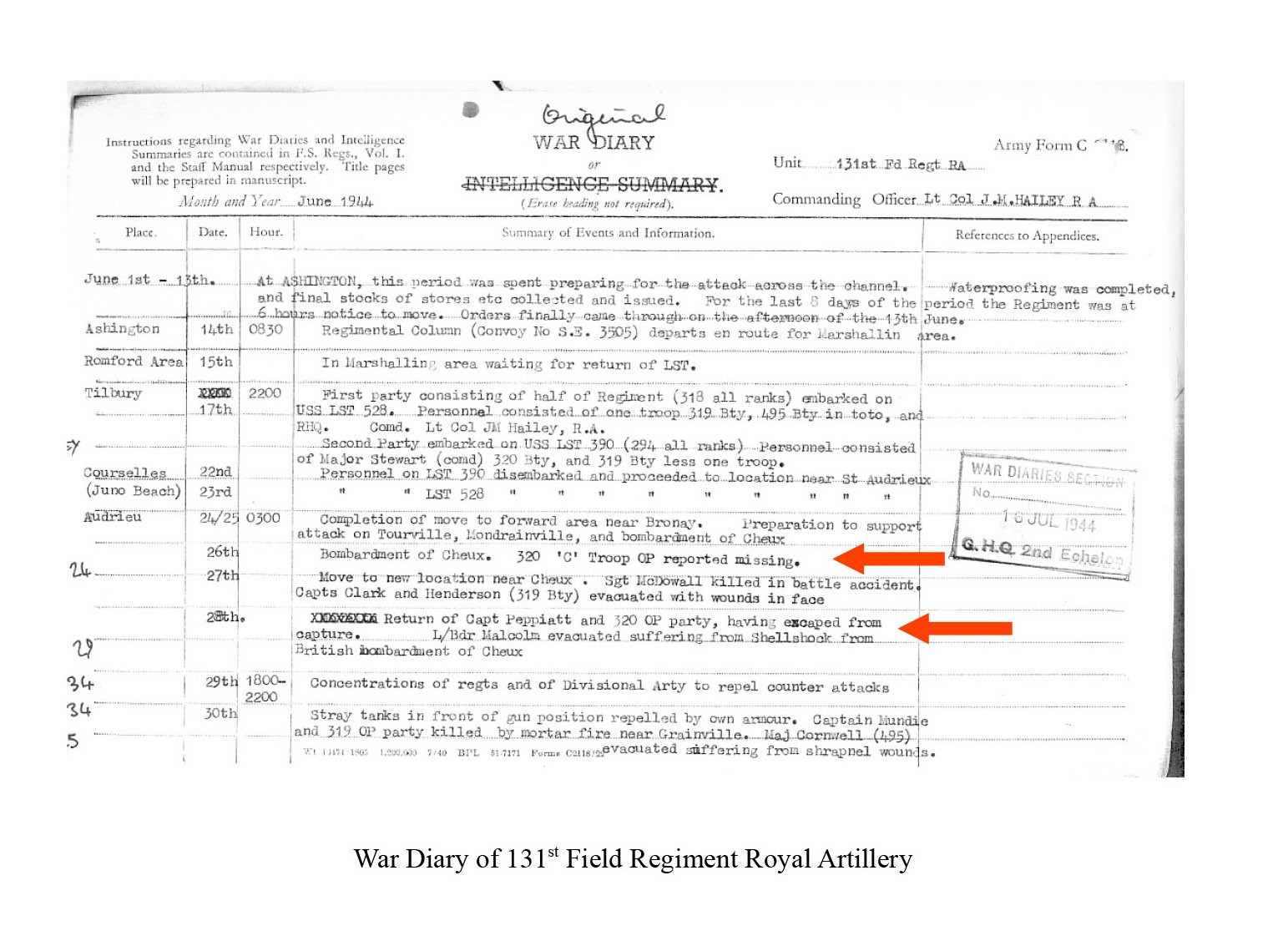

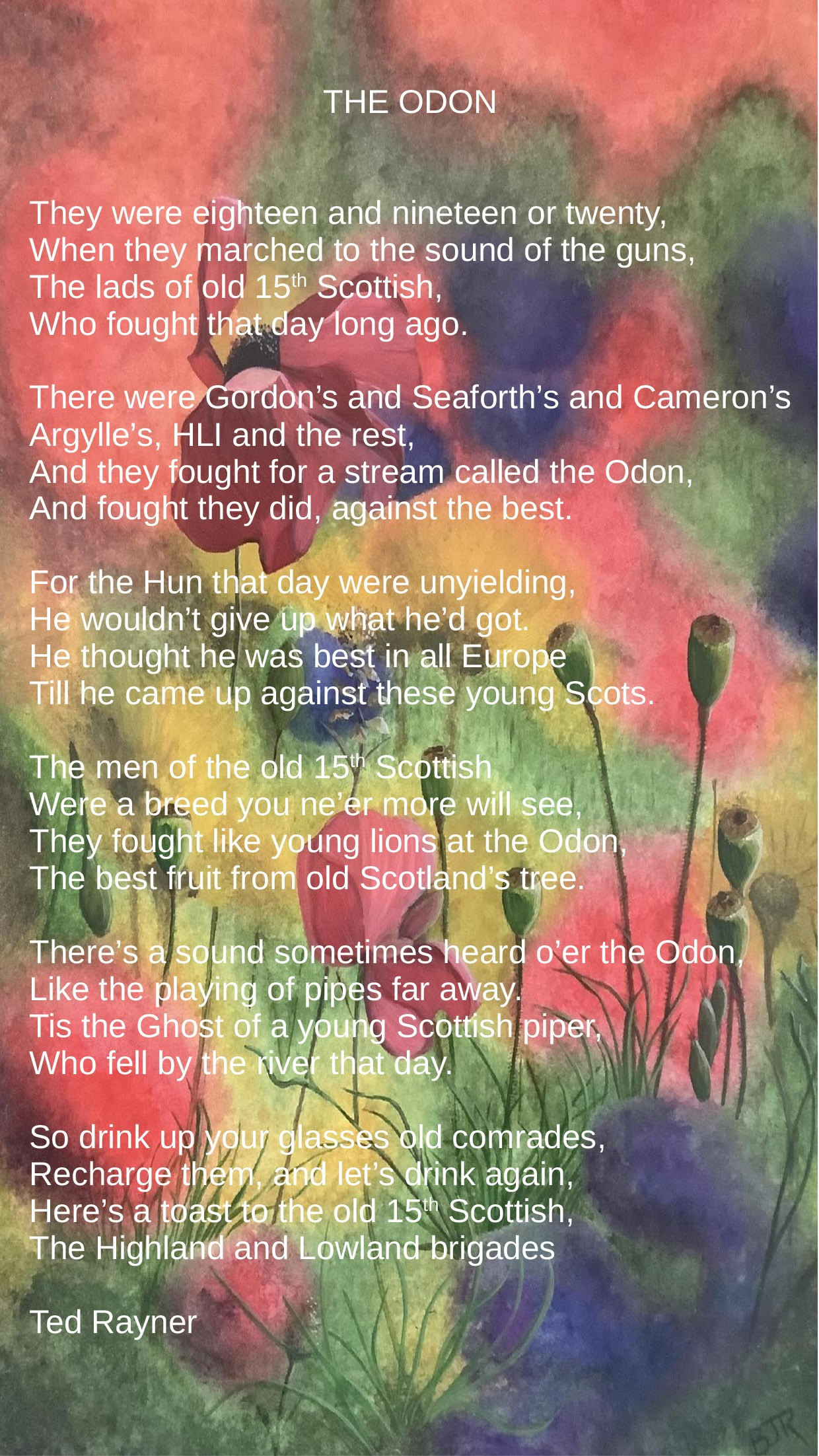

John Rayner has sent in this fascinating story written by his father, Gunner Edward (Tich) Rayner, who was heavily involved in the Battle for the Odon while serving with the 131st Field Regiment, Royal Artillery in June 1944.

Part 1: The Odon – Capture and Escape – by Tich Rayner

What follows is an account of a battle from D-Day plus, in Normandy 1944. The participants were:

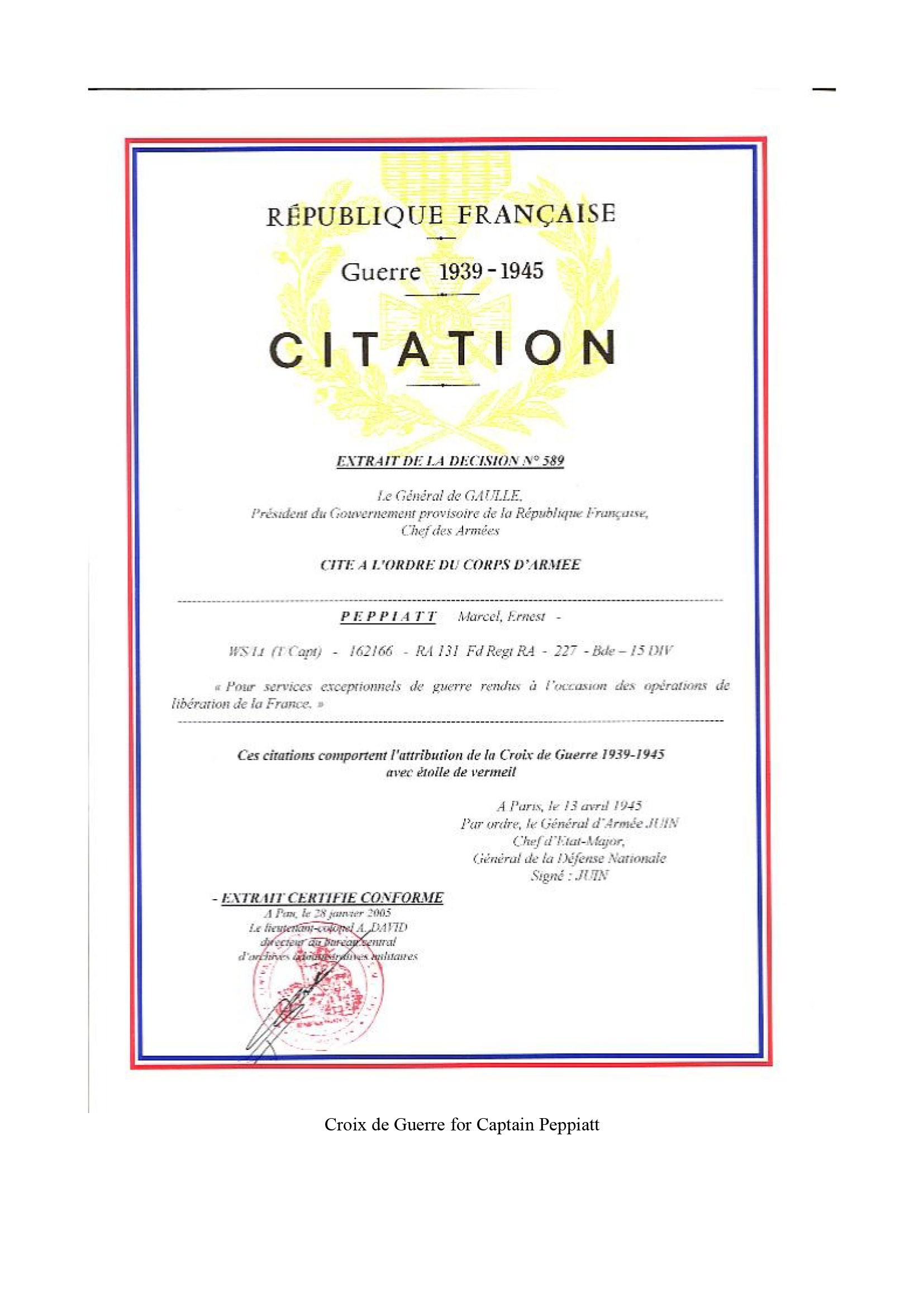

Capt. Peppiatt – Forward Observation Officer

Gunner Tommy Gray – Wireless Operator/Bren Gunner/ Driver

Gunner Edward (Tich) Rayner – Wireless Operator/ Bren Gunner/Driver

Gunner Maurice Stennet – Driver

(All members of a Forward Observation Post of 131st Field Regiment, Royal Artillery).

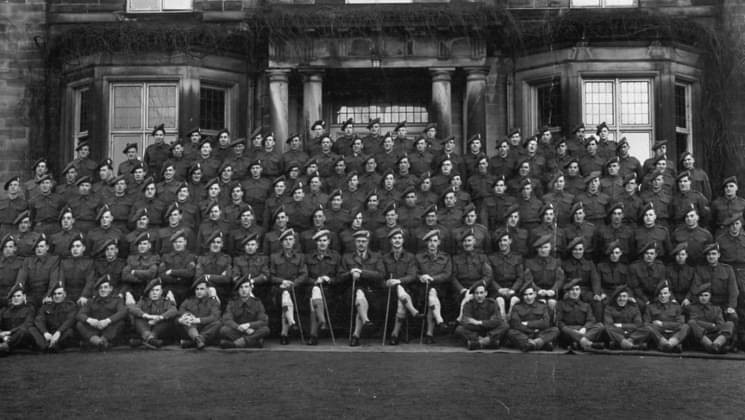

The night of 25 June and early morning of the 26 June 1944 was spent moving up with our infantry friends, in our case the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders. Over the training years we had got close to the Gordons and they to us.

At 0730hrs a tremendous bombardment of known enemy positions opened up, involving between 700 and 800 guns, including the guns of heavy naval units lying off the Normandy coast. The noise was ear splitting, but I was wearing my earphones clamped firmly on so it wasn’t too bad for me.

On Pep’s (Capt. Peppiatt our OC) orders I checked in with regiment to make sure all was well with communications. It was our sister brigades’ turn, the 44th and 46th. They were by now committed to battle as we could hear the rattle of the bren guns and the bang of tank shells interspersed with enemy machine guns and the crash of German mortar fire from multi-barrelled pieces, known to the British troops as Moaning Minnies for the horrible noise they made in flight. It was obvious to us that a terrible battle was developing just ahead of us and it was not long before we were committed.

We were approaching the village of Cheux when a three-ton truck full of ammunition just ahead of us was struck by an enemy shell and exploded into a ball of fire. Sergeant McDowell who had been following us on his motorbike, closed up to our carrier for cover.

Cheux was a shambles. Vehicles of every type crowded the one narrow street. Snipers were everywhere, while mortars crashed down all around us causing chaos and destruction and spreading confusion all around.

We cleared the village and found ourselves in a sunken lane. Bocage country. We had heard about it and now we were in it. As we went along we came across a medical station in which the medics of the Gordons had set up and were performing minor miracles for the wounded of both sides that the stretcher bearers brought in. Now we had to find our company, A-company. They had got through Cheux quicker than us, as we were on foot.

Suddenly we were called up by the CO of the Gordons, who told us that “A” company would be in Collville by now, the next village on, and to get ourselves up there as quickly as possible. Ahead of us lay a narrow lane blocked by a dead cow. A quick look at the map showed us we were on the right route.

Quickly, Pep told the driver to drive over the poor cow and drive on. The road we took from Cheux to Collville was really a country lane. It went straight for about 300 yards, then took a 90-degree left turn, then another 500 yards into Collville.

On our left as we proceeded was a large wood. On the right side there was an extensive corn field. As we slowed down for the sharp turn it occurred to us that we were alone. We saw no one ahead of us. It was as if we were driving down an English country lane. The battle in Cheux now seemed remote and unreal. Indeed we could have been on exercise in England.

However, this all changed the moment we turned the corner, for there in front of us less than 50 yards away was a company of German SS infantry advancing towards us. Who was the more surprised at this moment we will never know.

In a flash Pep ordered our driver to return the way we had come, and as we hightailed it back, a section of the enemy was waiting for us, armed with Panzerfausts. They let fly and took the track off our bren carrier. We were prisoners of war.

Our captors were elated, while we were in complete shock, white-faced and speechless. We were made to climb out of our carrier, disarmed and ordered to sit on the road-bank.

It wasn’t long before another carrier came along the road from Cheux. It was only minutes behind us. It was a vehicle from the Gordon Highlanders and we watched in horror as the Germans destroyed it with clinical efficiency, killing all the crew. There was nothing we could have done. The whole business made us even more depressed and aware of our own precarious situation.

It was getting dark when the Germans decided to move us out. We were marched through into Collville, where a large vehicle towing an artillery piece picked us up and took us behind German lines.